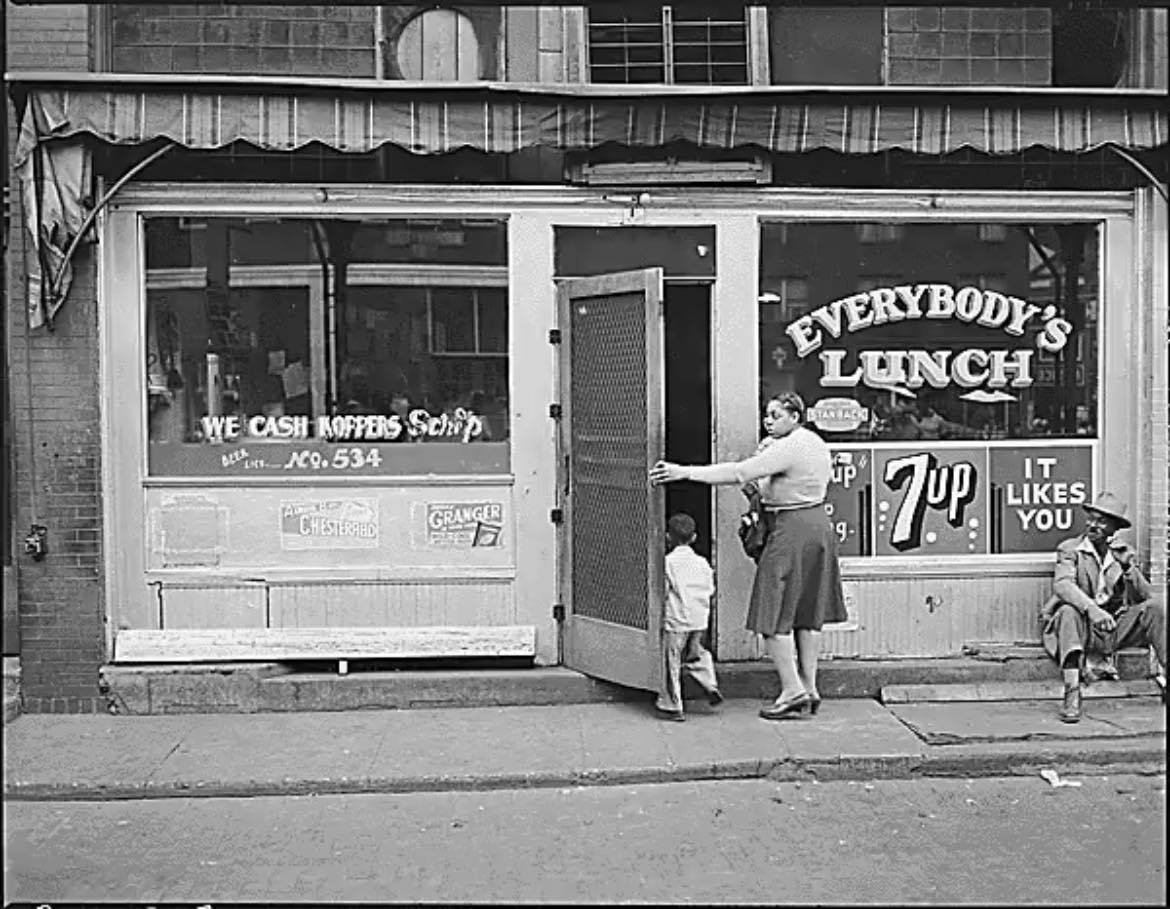

I just found this photo and I’m in love with it because this picture truly says a thousand words, as the old saying goes.

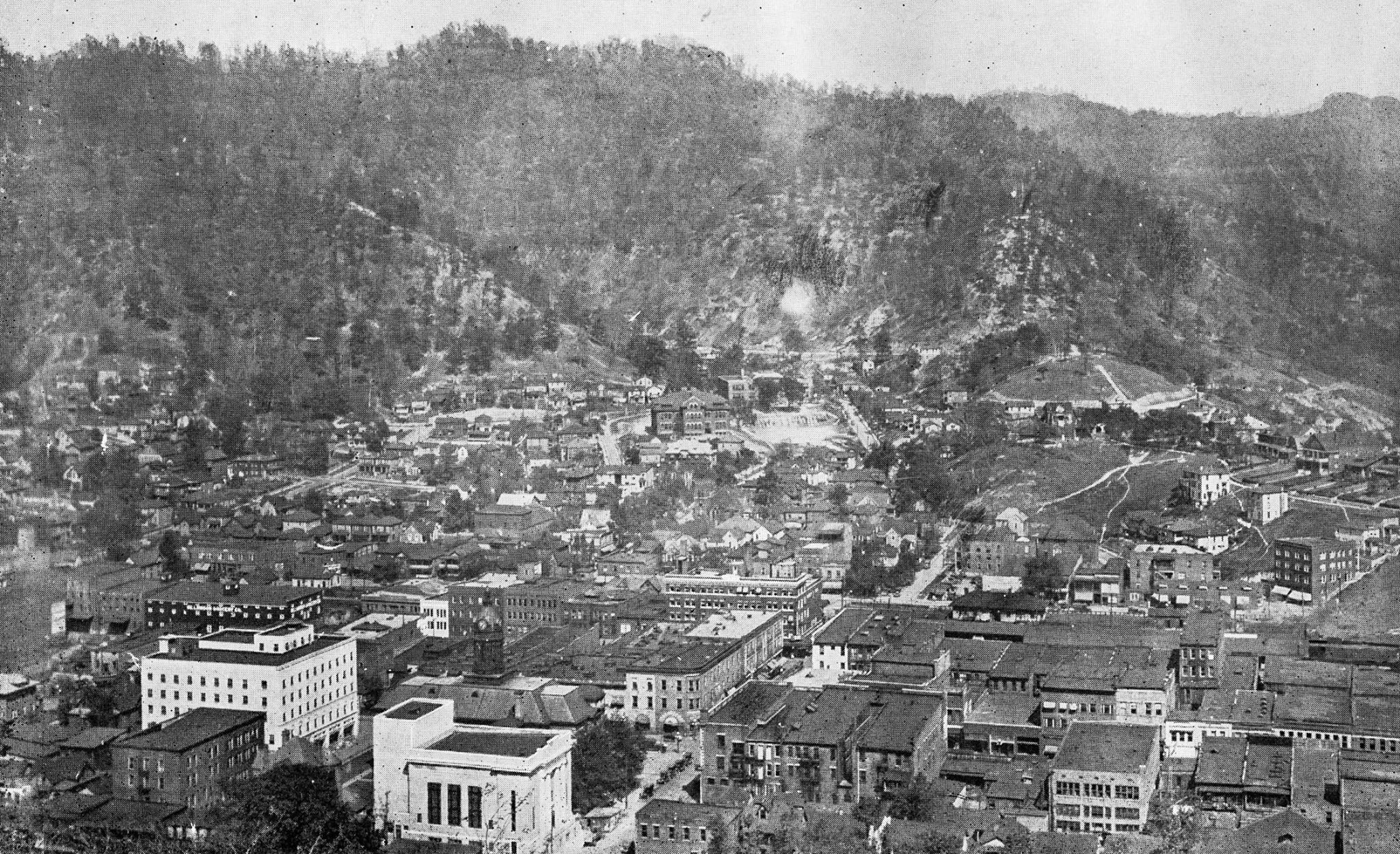

It is from Welch, West Virginia in the 1940s. The first thing that jumped out at me was the writing on the lower left of the restaurant’s window. It says “We Cash Koppers Scrip” – a reference to the scrip issued to miners rather than cash from the Koppers Coal Company for use in their company stores to purchase food, clothing, and other basic necessities.

Scrip was initially not transferable until the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 outlawed the practice, which had previously completely locked in a miner to spending the scrip in the company store without option. Local businesses took advantage of the change in law to offer cash in exchange for scrip (at a cost, of course). Of course, it wasn’t nearly as beneficial in those instances where the coal camp was so remote that the town couldn’t sustain an alternative to the company store.

The practice of using scrip was finally banned altogether in 1967.

Not coincidentally, the establishment lists its beer license right under that statement as beer wouldn’t have been available in the company stores. They say necessity is the mother of invention but time has revealed to me that profit must be the father of invention. Sadly, alcohol has always been a factor in the coalfields. where the men toiled long days doing backbreaking work who were often desperate for some type of escape from the pain in their bodies or the loneliness in their minds. This demand for alcohol married with local businesses cash registers to create a new way for coal miners to lose the value of their hard-earned dollars, as these scrip exchanges came with a fee.

I would also like to point out how well-dressed the gentleman is sitting on the stoop. It was an different era in so many ways – days that have truly gone by.

The coal boom has passed and the scrip system has long been a memory so it is great that folks took the time to capture these moments on camera for us all to see and learn from.